Well, my perfect track record of hitting complications and failing to find a workaround continues.

I have been able to figure out draping/rubbersheeting, but I have not been able to convert that file into something readable so that I can post it to this blog. I have tried converting the file from .dsx (I exported it from NSD first) into a .pdf but my Illustrator keeps going down; I suspect my laptop can’t handle the task. So tonight or tomorrow I’ll got to campus and try and find a work station to do that at.

[edit: SUCCESS!]

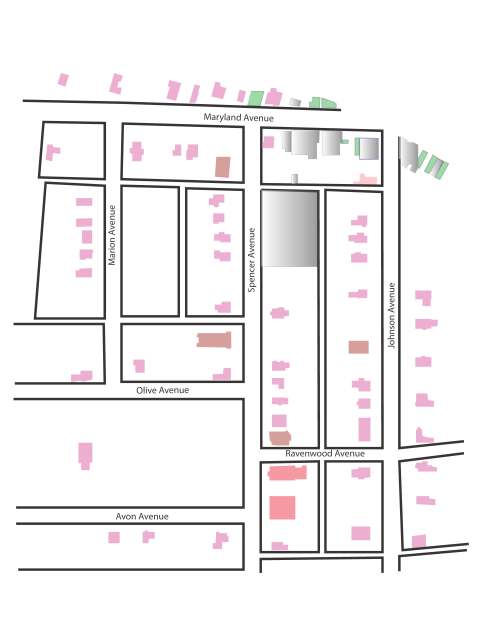

I learned a few things from this process; one thing is that these files get pretty big. I also learned that by putting a topographic map over a terrain map, I can make the visual information about elevation and slope much clearer and of course this makes the camera view much more illuminating. I will try to put together a better, more comprehensive map for our atlas project (this one is really small) but at least I’ve tackled the basic technical issues despite the hiccups I’ve experienced.

Last night, on a whim I decided I should try and do the architectural reconstruction project in case I was unable to solve the issue with exporting my map. I decided to try the Aldie Mill, which is a three-building complex in Aldie, Virginia, which was the endpoint of the Little River Turnpike and an important center for flour and meal production in northern Virginia. Two turnpikes connected the farms of the Shenandoah Valley to the Aldie Mill, so a great deal of the flour delivered to the port of Alexandria came from here. My thinking was–I hadn’t put much time into Sketchup but I found it reasonbly intuitive, so I thought what the heck, I’ve got a few hours and the Aldie Mill is a pretty basic brick structure–let’s go for it.

Well, I was right about the mill buidings–I was able to knock those out reasonably quickly, after wasting FAR too much time sweating the exact size. Being that they are square brick buildings with stone foundations and tin roofs, it wasn’t long before I had the basic buildings placed in roughly to-scale proximity to each other. I even found a reasonable model of a waterwheel through the 3D warehouse. It took awhile to get going, and it was already a little later than I would have liked, but I thought I was on the way to having a really good model.

But after a little while, I realized I’d made a couple of errors. One–because I’d seen pictures of the mill online, I assumed that those pictures would suffice for a full reproduction, especially given that I’ve actually visited the site. However, I quickly realized that the bulk of those online pictures are of the same few views. There are no views I could find from the north end, nor of the retaining pond which feeds water into the trough over the wheels. I was able to get ample views of two of the three buildings, and at least two sides of the third (northernmost) building, but by waiting to the last minute I had prevented myself from getting enough visual information to make all aspects of the model accurate.

Secondly, I struggled a great deal with how to show the foundation and the lower walls on the south side, where the wheels are and the canal carrying water away from the mill back to the Little River is. I wasted a great deal of time on aborted, sloppy work-arounds, which was frustrating because up to that point my work had been, if not skillful or particularly elegant, at least I was utilizing the functionality of Sketch Up in a rational way. But now I was just drawing things in hopes of “faking” a cohesive answer to what was clearly both a conceptual and a technical shortcoming on my end.

Ultimately I realized that what I should have done was to have started with a ground cover of some kind; then I could have marked out a canal path and lowered it, and filled in the stone walls and so forth from there. Doing so would have not only been the more efficient solution. However, my lack of a good picture of the retaining pond, how it feeds into the trough, and the entire north side of the complex probably doomed my efforts.

I finally gave up on the project when I realized that when all was said and done, the mill itself is still standing and while some external features recorded in pictures no longer exist, a modern photograph of the current structure will more than suffice for a visual representation. Given that there’s only a month left in the semester, I will simply present what’s left of my ‘working draft’ without further comment:

Caption: “The big thing with a blue top was going to be a retaining pond.”

Do I regret spending last evening on this failed venture when time is pressing? Not really. I did learn a few things about Sketch Up, and while I don’t think my project really calls for any architectural reconstruction, that’s not to say I won’t someday find a use for this skill. I still have a lot to learn, but I learned quite a bit even from this failure, and I mostly learned that Sketch Up is not an intimidating product to use. It just takes time, and a good understanding of what it is you are setting out to do. Last night, I had very little of the former, and not quite enough of the latter. Lesson learned, and now it’s time to move on.

Above: The main (middle) building of the Aldie Mill. I had hundreds of pictures of this view, but not a single one of the north end of the complex. I need to take my camera next time I’m in the neighborhood.